Rethinking Least Squares: Min-Norm Solutions and Loss Geometry

Machine Learning Fundamentals for Economists

Overview

Motivation

- In preparation for the ML lectures we cover some core numerical linear algebra concepts on functional equations

- We will also use this as an opportunity to reinterpret least squares solutions as a prelude to non-linearity

- Connection to previous lecture: conditioning and eigenvalues drive algorithm behavior

Why This Matters for ML

- Modern ML operates in high-dimensional parameter spaces where traditional “identification” fails

- Neural networks: millions of parameters, infinitely many equivalent solutions

- Yet these models generalize well despite apparent non-uniqueness

- Key insight: multiplicity of parameters \(\neq\) multiplicity of the functions they represent

- Different \(\beta\) may produce the same (or nearly same) predictions

- Understanding this requires thinking about geometry of loss functions

- This lecture builds intuition through the simplest case: linear least squares

- Same geometric principles extend to deep learning

Packages and Materials

Least Squares with the QR Decomposition

Least Squares and Normal Equations

- Given the least squares problem

\[ \min_x \| Ax -b \|^2 \]

- Taking the FOCs and rearranging gives the normal equations

\[ A^\top A x = A^\top b \quad \Rightarrow \quad x = (A^\top A)^{-1} A^\top b \]

- This works, but forming \(A^\top A\) can be numerically unstable

- Condition number squares: \(\kappa(A^\top A) = \kappa(A)^2\)

QR Decomposition for Least Squares

- QR factorizes rectangular matrices: \(A = Q R\) for \(Q\) orthogonal, \(R\) upper triangular

- Substitute \(A = QR\) into the normal equations \(A^\top A x = A^\top b\):

\[ (QR)^\top (QR) x = (QR)^\top b \]

\[ R^\top Q^\top Q R x = R^\top Q^\top b \]

- Since \(Q^\top Q = I\) (orthogonal), this simplifies to \(R^\top R x = R^\top Q^\top b\)

- Left-multiply by \((R^\top)^{-1}\) to get the triangular system:

\[ R x = Q^\top b \]

- Solve via back-substitution - avoids forming \(A^\top A\) entirely, much more stable

QR is Used Internally for Least Squares

- Inside

lstsqand similar functions, QR is used for numerical stability - Compare direct normal equations vs. QR-based solution

N, M = 10, 3

A = np.random.randn(N, M) + np.random.randn(N, 1)

b = np.random.randn(N)

# QR-based solution

x_lstsq, residuals, rank, s = lstsq(A, b)

# Normal equations (less stable but instructive)

x_normal = solve(A.T @ A, A.T @ b)

print(f"lstsq solution: {x_lstsq}")

print(f"Normal eqn sol: {x_normal}")lstsq solution: [-0.4229563 0.63714154 -0.16902314]

Normal eqn sol: [-0.4229563 0.63714154 -0.16902314]QR and Underdetermined Least Squares

- Take the case where \(N < M\) and use the QR decomposition

Solution: [-3.05555556 0.11111111 3.27777778]

Rank: 2, Columns: 3- Wait, why did that give an answer?

- And if I try various algorithms even with random starting points, why does it give the same answer?

- There is a bias towards a particular solution. Will come back to this repeatedly

Min-Norm Solutions and Sobolev Spaces

Min-Norm Solution

- Linear least squares was solving \(\min_x \| Ax -b \|_2^2\)

- Which had multiplicity in this case. The solution it returns fulfills

\[ \min_x \| x \|_2^2 \quad \text{s.t.} Ax = b \]

- Or, can think of as solving the “ridgeless regression”

\[ \lim_{\lambda \to 0}\left[\min_x \| Ax -b \|_2^2 + \lambda \| x \|_2^2\right] \]

- Will become crucial in deep learning where the number of parameters \(\gg\) data

Algorithms + Optimization Problems

- A key requirement to make the switch to ML thinking is to remember that just seeing the optimization problem, e.g. \(\max_{x} f(x)\) may not be enough

- The algorithm itself will be important if there is multiplicity in solutions, if things are not numerically stable, etc.

- In the case above, we saw that using QR decomposition delivered the min norm

Linear Operators, not Matrices

- Recall: for \(x \in {\mathbb{R}}^N\) we should think of \(f(x) = A x\) for \(A\in{\mathbb{R}}^{M \times N}\) as a linear transformation from \({\mathbb{R}}^N\) to \({\mathbb{R}}^M\)

- Definition of Linear: \(f(a x_1 + b x_2) = a f(x_1) + b f(x_2)\) for scalar \(a,b\)

- Many algorithms might be implementable just using the matrix-vector product or the transpose of the matrix-vector product?

- Maybe we don’t actually need to create a matrix? Can compose operations together?

- This will be related to a lot of ML algorithms and autodifferentiation. Hint: Jacobian \(\nabla f(x) = A\)

- The key to iterative methods will be the spectral properties of the Jacobian, which is related to the eigenvalues of \(A\)

\(L^p\) Space

Let \(\Omega\) be an open subset of \({\mathbb{R}}^n\). A function \(u: \Omega \rightarrow {\mathbb{R}}\)

\(L^p(\Omega)\) space: A function \(f: \Omega \rightarrow {\mathbb{R}}\) is in \(L^p(\Omega)\) if:

\[ \int_\Omega |f|^p \, dx < \infty \]

- Useful in a lot of cases, but will be especially important when considering norms on a function space and whether a particular function solves a particular problem

Sobolev Space

A function \(u\) belongs to the Sobolev space \(W^{k,p}(\Omega)\) if:

\[ u \in L^p(\Omega) \]

and all its weak derivatives up to order \(k\) are also in \(L^p(\Omega)\).

A function \(\phi \in W^{k,p}(\Omega)\) is said to be a weak derivative of \(u\) if:

\[ \int_\Omega u D^\alpha \phi \, dx = (-1)^{|\alpha|} \int_\Omega \phi D^\alpha u \, dx \]

for all multi-indices \(\alpha\) with \(|\alpha| \leq k\).

Sobolev Norm

The Sobolev Norm for a function \(u \in W^{k,p}(\Omega)\) is defined as some variation on:

\[ \| u \|_{W^{k,p}(\Omega)} = \left( \sum_{|\alpha| \leq k} \int_\Omega |D^\alpha u|^p \, dx \right)^{1/p} \]

where \(\alpha\) is a multi-index and \(D^\alpha u\) represents the weak derivative of \(u\).

You can choose whatever terms you want in \(\alpha\)

A Key Sobolev Semi-Norm

The key one to keep in mind is \(W^{1,2}(\Omega)\), which is the space of functions with square-integrable first derivatives.

\[ \| u \|_{W^{1,2}(\Omega)} = \left( \int_\Omega |\nabla u|^2 \, dx \right)^{1/2} \]

- Note that we have the option to include or not include the \(|u|^2\) term itself when we define a particular norm

- This is a semi-norm because it is semi-definite (i.e., multiple \(u\) with \(\|u\| = 0\))

- Semi-norms serve two key purposes: establish equivalence classes, and prove a way to control length which will come up with algorithms

Sobolev Semi-Norms and Equivalence Classes

- A Sobolev semi-norms \(S\) define equivalence classes of functions

- i.e., any \(u_1\) and \(u_2\) such that \(\|u_1 - u_2\|_S = 0\) are in the same equivalence class

- In general, when we move to nonlinear and highly parameterized models there will be many solutions that are equivalent

- But if they are in approximately the same equivalence class, then who cares?

- Multiplicity of “parameters” doesn’t really matter if the functions do the same thing

Sobolev Semi-Norms and Occam’s Razor

- The other purpose is to give some sense of length, \(\|u_1\|_S < \|u_2\|_S\)

- This will come up with regularization since we may want to bias algorithms towards particular functions or interpret inherent bias in the algorithms

- The key interpretation here is that for Sobolev Norms we can think of variations on the \(W^{1,2}\) as determining how simple a function is

- If \(\|u_1\|_S < \|u_2\|_S\) then it has smaller gradients and fewer “wiggles”

- If both interpolate the same data, then we should prefer the simpler one. Occam’s Razor

- We won’t always be able to know the precise semi-norm when working with ML, but this is useful intuition

Sobolev Norms and Linear Functions

- Now, think of linear functions \(f(x) = \beta x\) where \(\beta\) is a vector, matrix, or scalar

- Consider this on a bounded domain \(\Omega\) so the integrals are well defined

- Then our Sobolev 1,2 norm, \(W^{k,p}\) here is simple:

\[ \|f\|_{W^{1,2}} = \|\beta\|_2 \]

Where \(\|\beta\|_2\) is euclidean norm of the vector, or the Frobenius norm of the matrix

Back to the Ridgeless Regression

Now lets reinterpret our “ridgeless regression” with a

\[ \lim_{\lambda \to 0}\left[\min_{\beta} \| A\beta -b \|_2^2 + \lambda \| \beta \|_2^2\right] \]

- This says that we are “penalizing” the norm of \(f(x) = \beta x\) in the \(W^{1,2}\) sense

- The limit \(\lambda \to 0\) means we are asymptotically dropping this penalty, but there is still this “bias” which makes solutions unique

- Normally unique to an equivalence class with in \(W^{1,2}\), but with linear functions they are unique. Why?

Min-Norm Solution as Occam’s Razor

Recall that this was also

\[ \min_{\beta} \| \beta \|_2^2 \quad \text{s.t.}\, A\beta = b \]

- i.e., we are finding the minimum norm solution that interpolates our data

- And we can interpret the minimum norm through Occam’s Razor

- This general principle will apply when we think about nonlinear approximations as well, though we don’t need to fully interpolate (i.e., if \(\lambda > 0\) then we don’t need to interpolate perfectly)

- Suggests the crucial role of regularization.

Singular Linear Systems of Equations

This isn’t just least squares

- Consider the case for finding solutions to \(A \beta = b\) where \(A\) is singular.

- Either no solution or infinite solutions exist

- If you solve a linear system with SVD or iterative methods it gives an answer! The min-norm solution

\[ \begin{aligned} \min_{\beta} & \,\| \beta \|_2^2\\ &\text{s.t.} A\beta = b \end{aligned} \]

Is the Min-Norm Solution Special?

The min-norm solution to LLS is the closest projection to the column space of the data

For a given norm it is the unique solution to a well-specified problem which can often be interpreted through appealing to simplicity

It is also the unique “most stable” solution for a given norm. Loosely,

- Take \(b + \delta b\) for some small \(\delta b\) and/or \(A + \delta A\) for some small \(\delta A\)

- Then the min-norm solution is the one where \(\beta + \delta \beta\) is smallest

Another interpretation we will apply to ML and nonlinear models: min-norm solutions are the ones least sensitive to data perturbations

This will also come up with Bayesian statistics, if we apply a prior which is asymptotically non-informative, the min-norm solution is the MAP solution

Min-Norm Solution and Conditioning

- As a preview of connections to the previous lecture, consider if the matrix is almost, but not quite singular

- Tough to know due to numerical roundoff

- You may have learned from experience that everything works great if you:

- Tweak to the diagonal of the matrix, or to the normal equations for LLS, or to make a covariance matrix positive definite

- Consider how that is related to the min-norm solution and L2 penalized LLS (i.e., “ridge”)

- Will turn out to be exactly equivalent in many algorithms

Geometry and Loss Functions

Geometry of Loss Functions

- The curvature of the loss function will be essential to understanding generalization

- The motivation: we will work with models where every local minima is a global minima, multiplicity is pervasive but innocuous, etc.

- For some \(\beta^*\) which is a local minima of \(\min_{\beta} f(X;\beta)\) the Hessian \(\nabla^2 f(X;\beta^*)\) tells us about whether minima are unique, how sensitive they are to perturbations, etc.

- Key questions to ask:

- What is the rank of the hessian? If full rank, with a positive definite hessian, then the solution is (locally) unique

- Eigenvalues show ridges/etc.

Geometry of Regularized LLS

\[ \min_{\beta} \underbrace{\frac{1}{2}\left[\| X\beta -y \|_2^2 + \lambda \| \beta \|_2^2\right]}_{\equiv f(X;\beta)} \]

- The Hessian is then (for all \(\beta\))

\[ \nabla^2 f(X;\beta^*) = X^{\top} X + \lambda I \]

- Is this problem convex with \(\lambda = 0\)? Only if \(X^{\top}X\) is positive definite

Reminder on Positive and Semi-Definite

Positive definite if \(x^{\top} A x > 0,\) (“semi-definite” if \(\geq 0\)) for all \(x \neq 0\)

With the spectral decomposition of symmetric \(A\)

\[ A = Q \Lambda Q^{\top} \]

- \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(\lambda_1, \ldots, \lambda_n)\) and \(Q\) is an orthogonal matrix of eigenvectors

- \(A\) is positive definite if \(\lambda_i > 0\) for all \(i\)

- \(A\) is positive semi-definite if \(\lambda_i \geq 0\) for all \(i\)

In more abstract and infinite dimensional spaces a linear operator \(A(x)\) operator is positive definite if \(x \cdot A(x) > 0\) for all \(x \neq 0\)

- Has eigenvalues/eigenvectors, i.e. \(A(x) = \lambda x\) for some \(\lambda\) and \(x\)

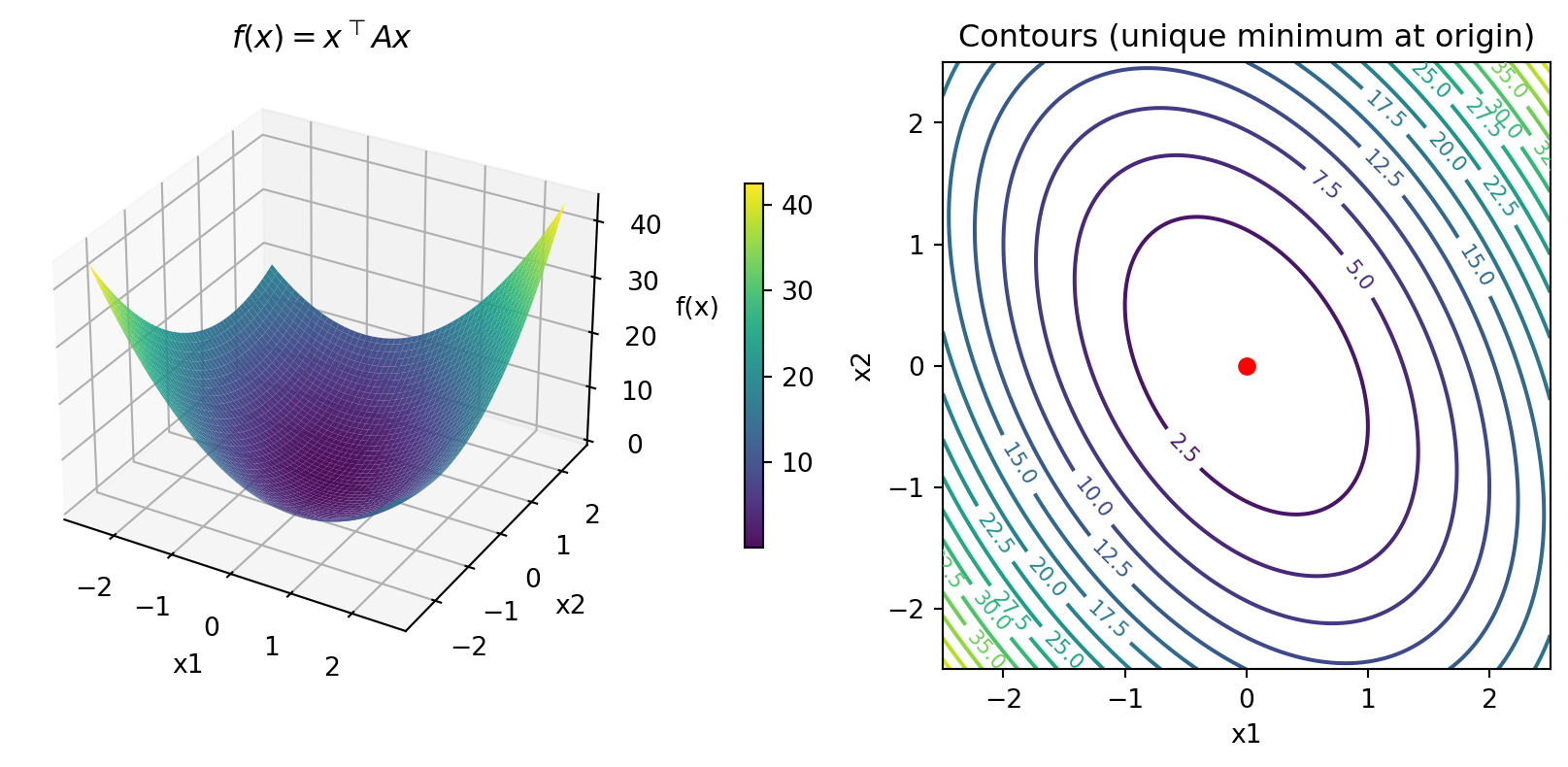

Shape of Positive Definite Function

- For \(A = \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 1 \\ 1 & 2\end{bmatrix}\) (positive definite)

- This has a unique minimum (at \((0, 0)\), since no “affine” term)

Eigenvalues: [1.38196601 3.61803399] (all positive)

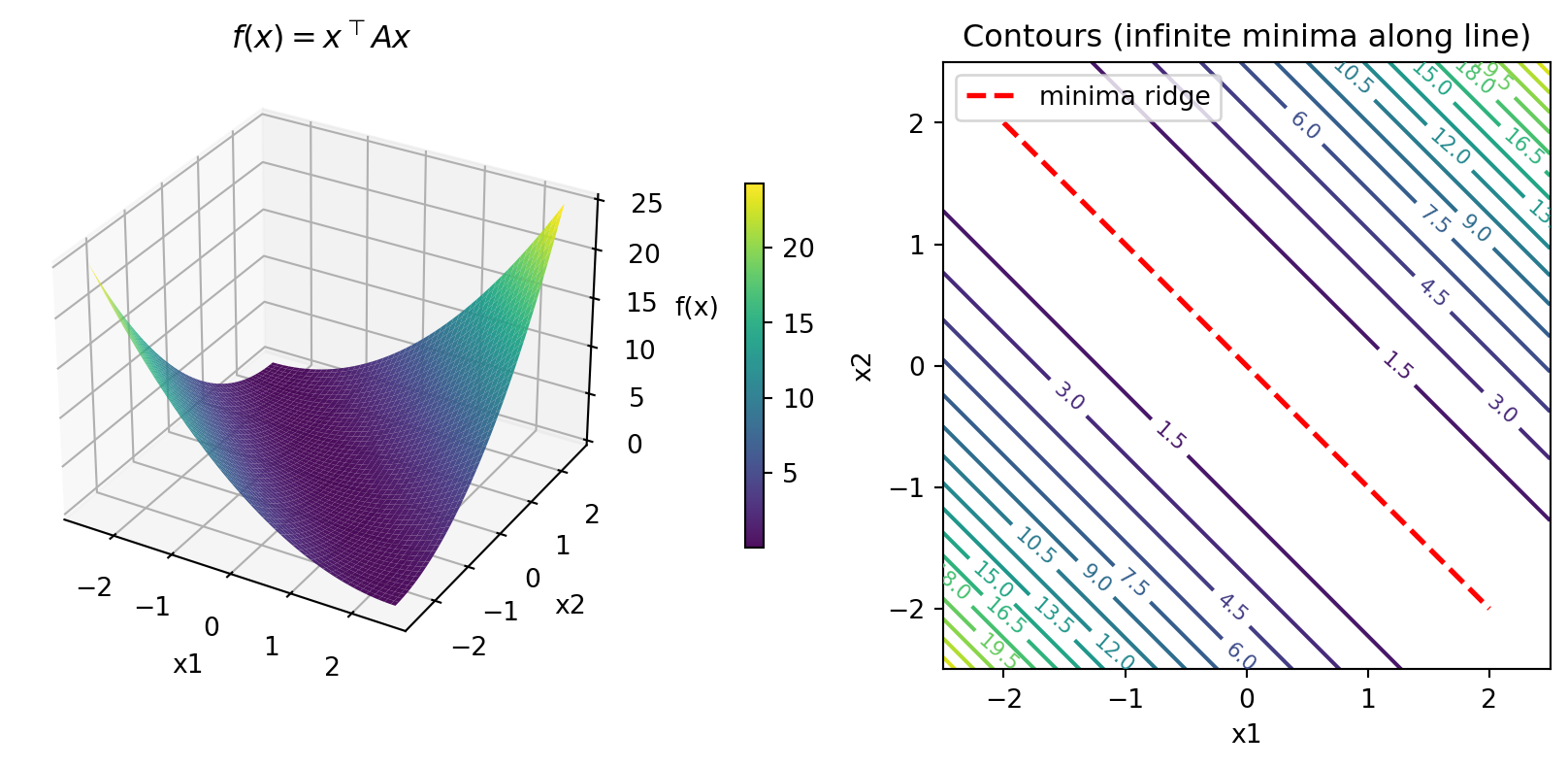

Shape of Positive Semi-Definite Function

- For \(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1\end{bmatrix}\) (positive semi-definite, not definite)

- Multiple minima along a line! The zero eigenvalue creates a “ridge”

Eigenvalues: [0. 2.] (one is zero!)

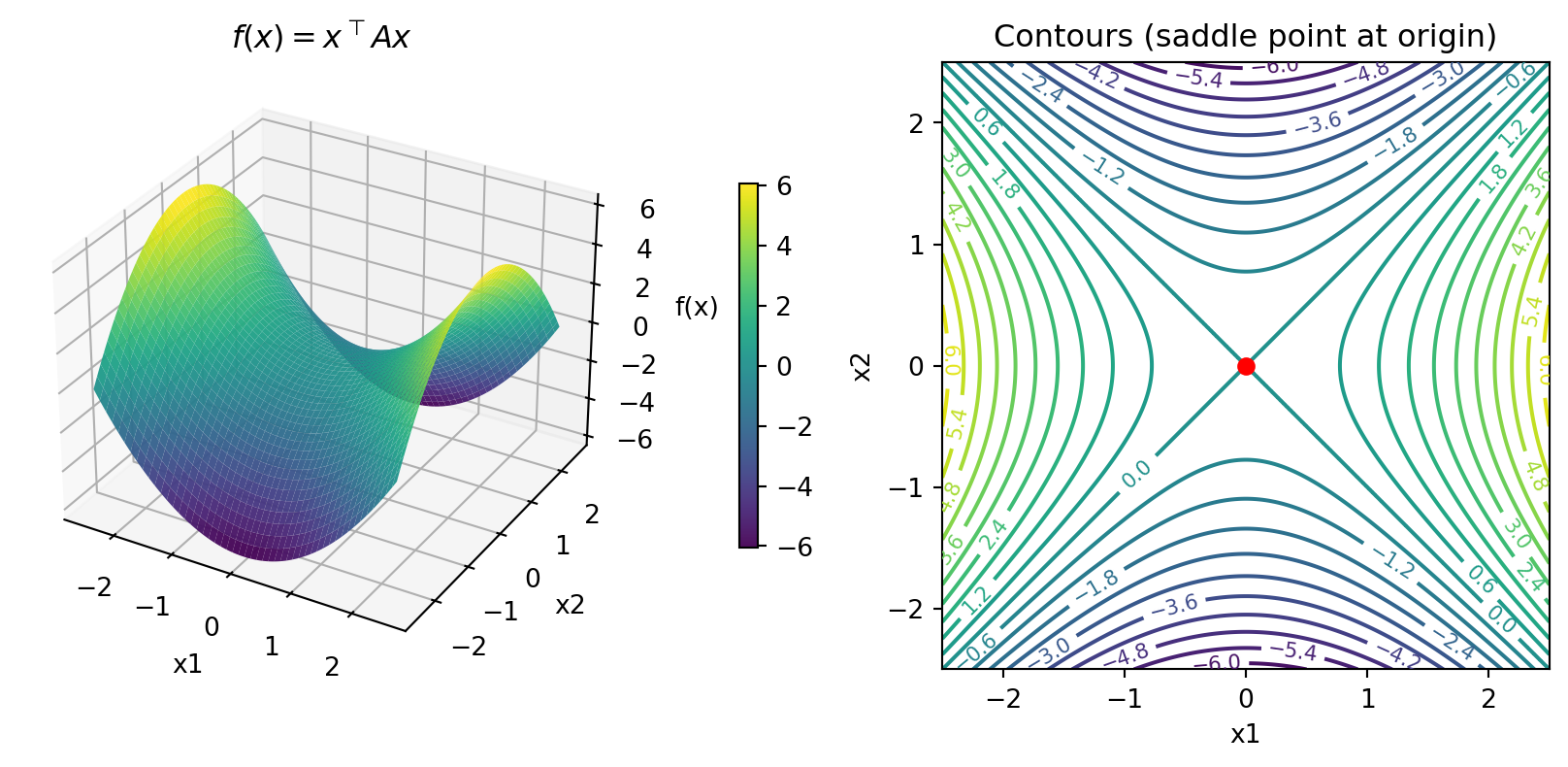

Shape of Indefinite Function (Saddle Point)

- For \(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1\end{bmatrix}\) (indefinite: positive and negative eigenvalues)

- No minimum or maximum at origin - it’s a saddle point

Eigenvalues: [-1. 1.] (mixed signs = indefinite)

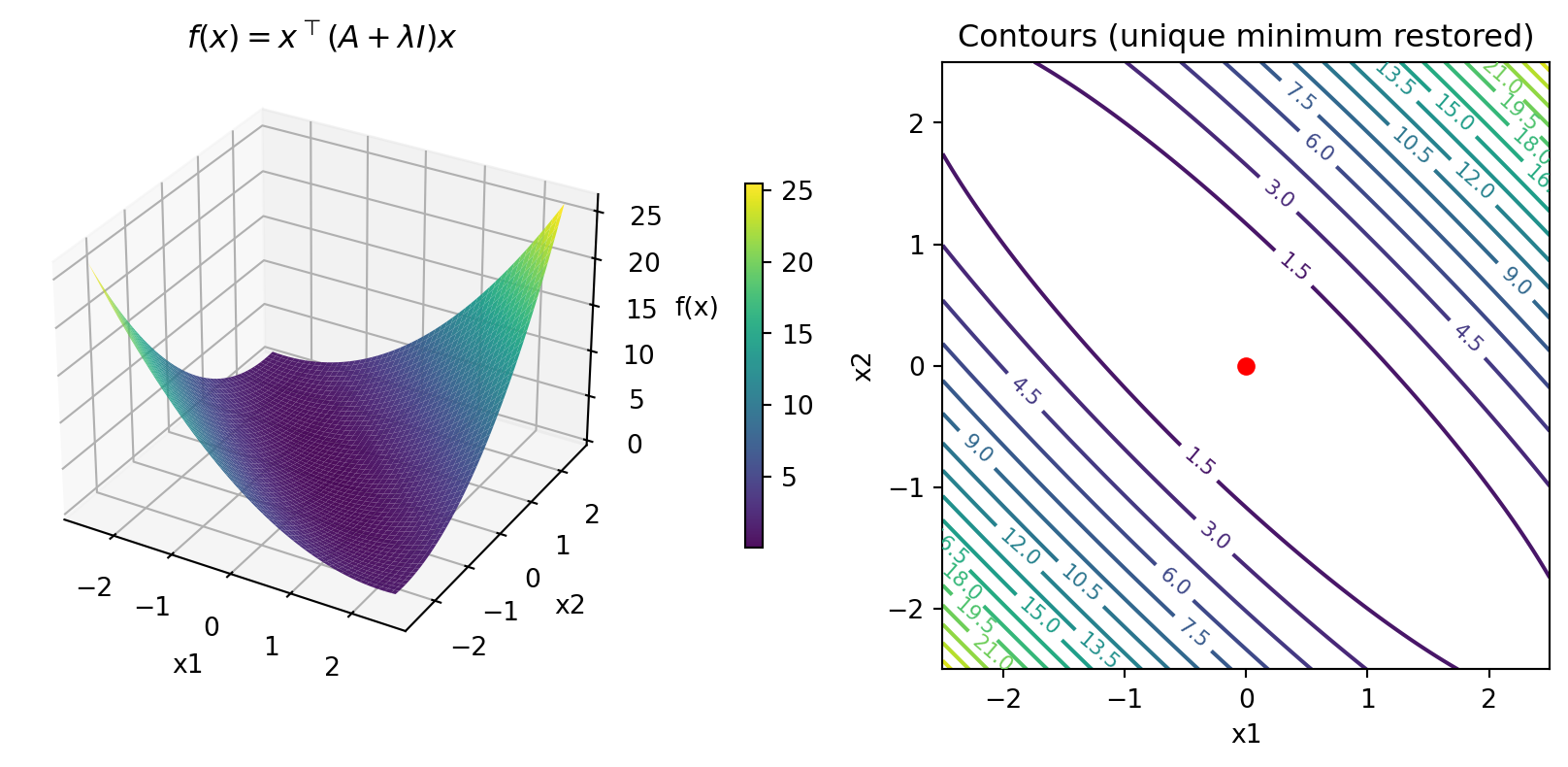

Regularization Creates Unique Minimum

- Take semi-definite \(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1\end{bmatrix}\) and add \(\lambda I\) for \(\lambda = 0.1\)

- Now unique minimum at \((0, 0)\)!

Eigenvalues after regularization: [0.1 2.1] (both positive now)

Convexity of a Quadratic Objective

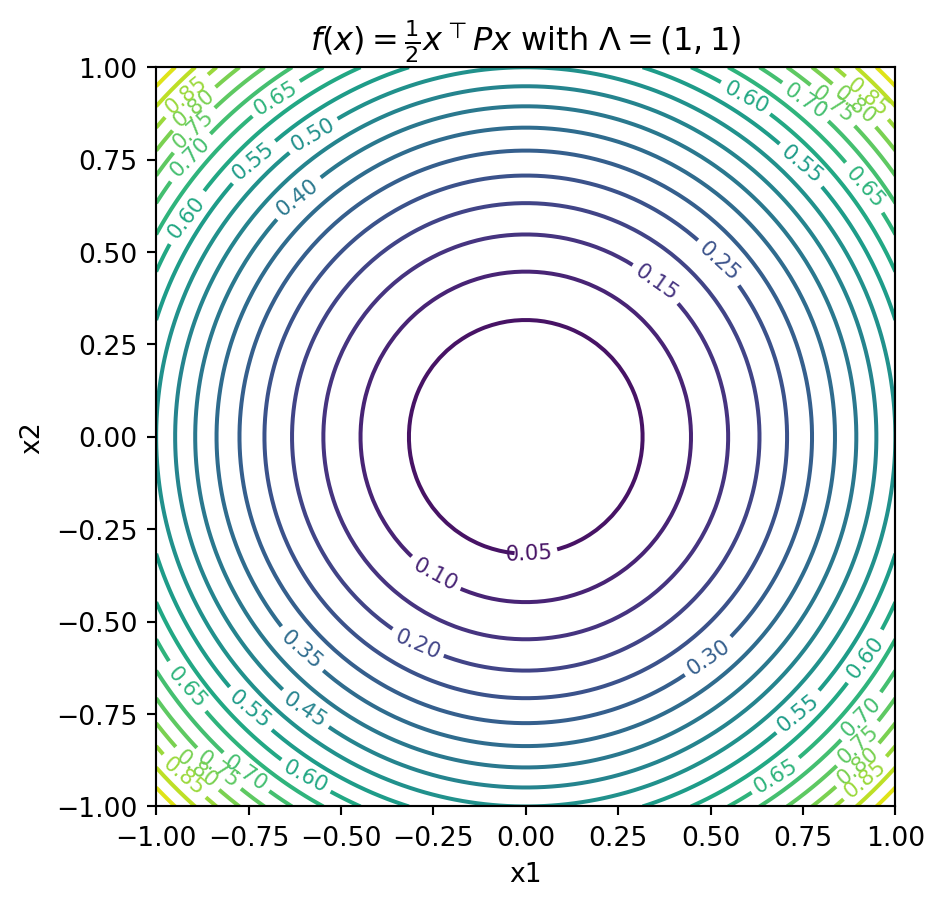

- We will build \(P\) and \(f(x) = \frac{1}{2}x^{\top} P x\) from the spectral decomposition

- Rotating eigenvectors and starting with \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(1, 1)\)

- And keep in mind that \(\nabla f(x) = P x\)

Contours of the Quadratic Objective

x_vals = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

X1, X2 = np.meshgrid(x_vals, x_vals)

Z = 0.5 * (P[0,0]*X1**2 + 2*P[0,1]*X1*X2 + P[1,1]*X2**2)

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 5))

cs = plt.contour(X1, X2, Z, levels=20, cmap='viridis')

plt.clabel(cs, inline=True, fontsize=8)

plt.xlabel('x1'); plt.ylabel('x2')

plt.title(r'$f(x) = \frac{1}{2} x^\top P x$ with $\Lambda = (1, 1)$')

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal')

Gradient Descent and Conditioning

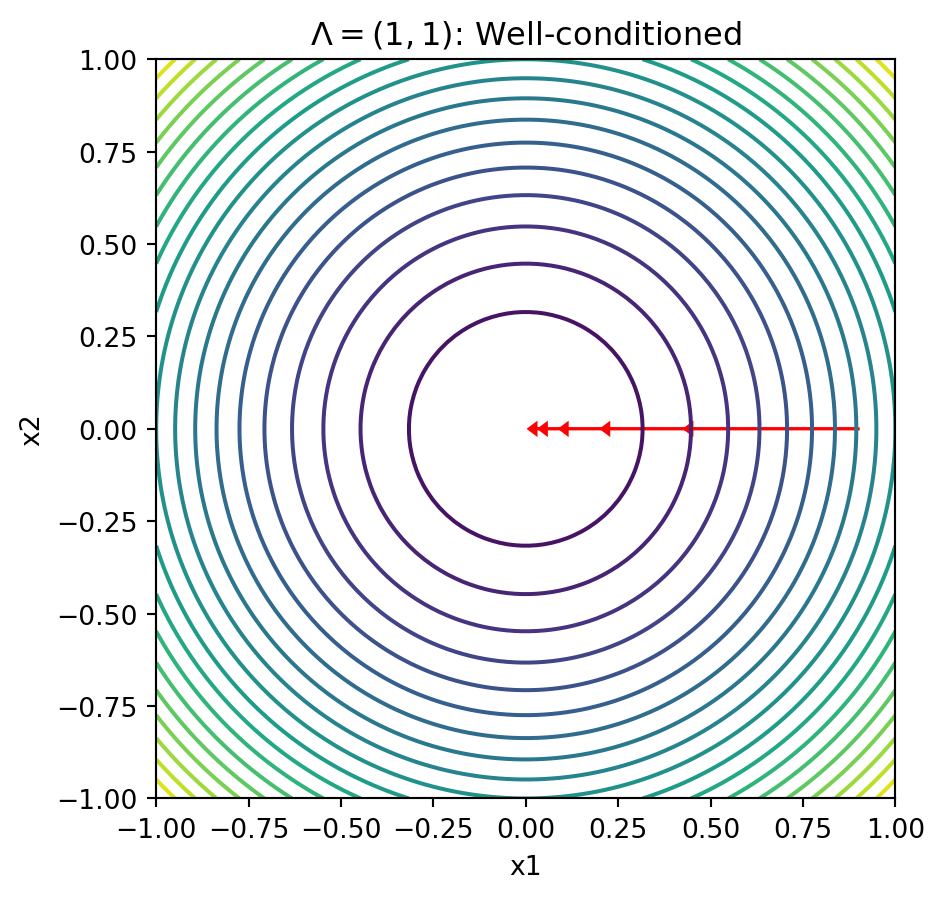

Gradient Descent Style Algorithms

- To understand the importance of geometry, lets consider optimizing with simple gradient descent style algorithms to minimize:

\[ \min_{x} \frac{1}{2}x^{\top} P x \]

- Let \(\eta > 0\) be a “step size”, learning rate, etc. then

\[ x^{i+1} = x^i - \eta \nabla f(x^i) = x^i - \eta P x^i \]

- We will fix \(x^0 \equiv \begin{bmatrix}0.9 & 0.0\end{bmatrix}\), set \(\eta = 0.5\) and plot a few iterations

Gradient Descent Visualization Code

def plot_gd_steps(N_steps, x_0, Lambda, eta):

Q = np.array([[np.sqrt(2)/2, np.sqrt(2)/2],

[-np.sqrt(2)/2, np.sqrt(2)/2]])

P = Q @ np.diag(Lambda) @ Q.T

gd_step = lambda x: x - eta * P @ x

x_vals = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

X1, X2 = np.meshgrid(x_vals, x_vals)

Z = 0.5 * (P[0,0]*X1**2 + 2*P[0,1]*X1*X2 + P[1,1]*X2**2)

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 5))

plt.contour(X1, X2, Z, levels=20, cmap='viridis')

x_current = np.array(x_0)

for i in range(N_steps):

x_next = gd_step(x_current)

plt.arrow(x_current[0], x_current[1], x_next[0] - x_current[0],

x_next[1] - x_current[1],head_width=0.03, head_length=0.02, fc='red', ec='red')

x_current = x_next

plt.xlabel('x1'); plt.ylabel('x2')

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal')

return plt.gcf()Contours With Well-Conditioned Matrices

- Let \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(1, 1)\) which leads to \(P = I\)

- Converges almost immediately. Immediately in any dimensions with \(\eta = 1\)

Contours With Well-Conditioned Matrices

Text(0.5, 1.0, '$\\Lambda = (1, 1)$: Well-conditioned')

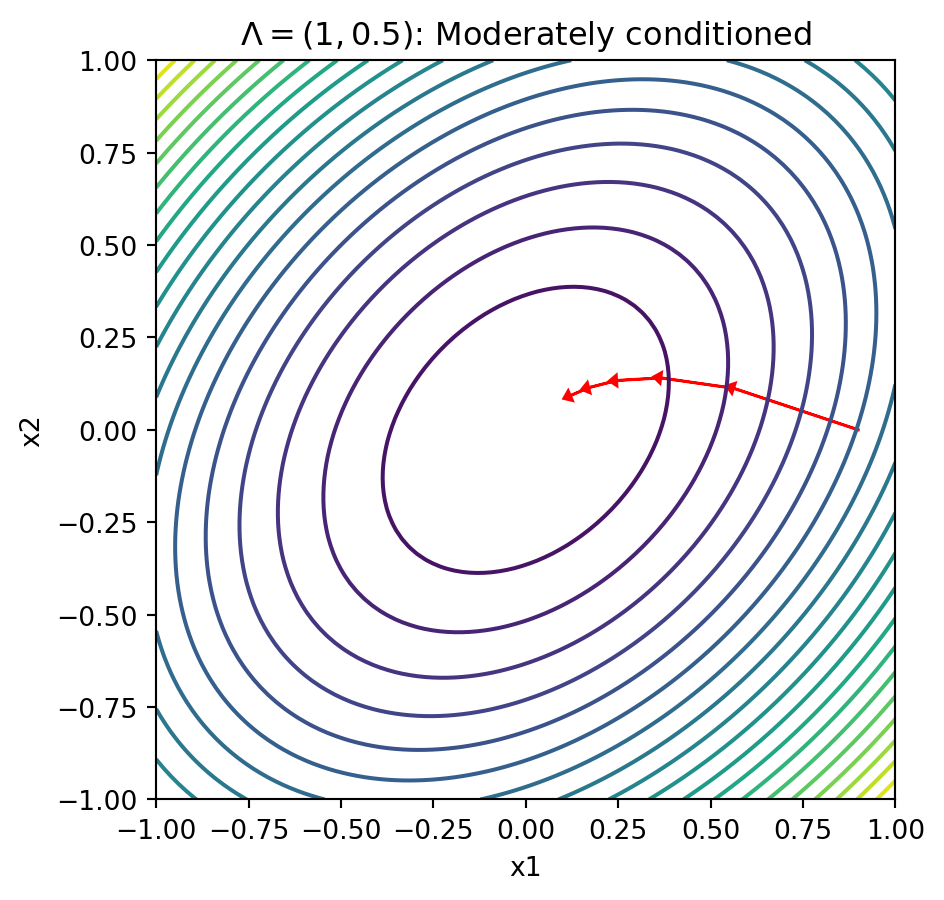

Contours With Less Well-Conditioned Matrices

- Let \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(1, 0.5)\)

- Does great in one direction, but slows down

Contours With Less Well-Conditioned Matrices

Text(0.5, 1.0, '$\\Lambda = (1, 0.5)$: Moderately conditioned')

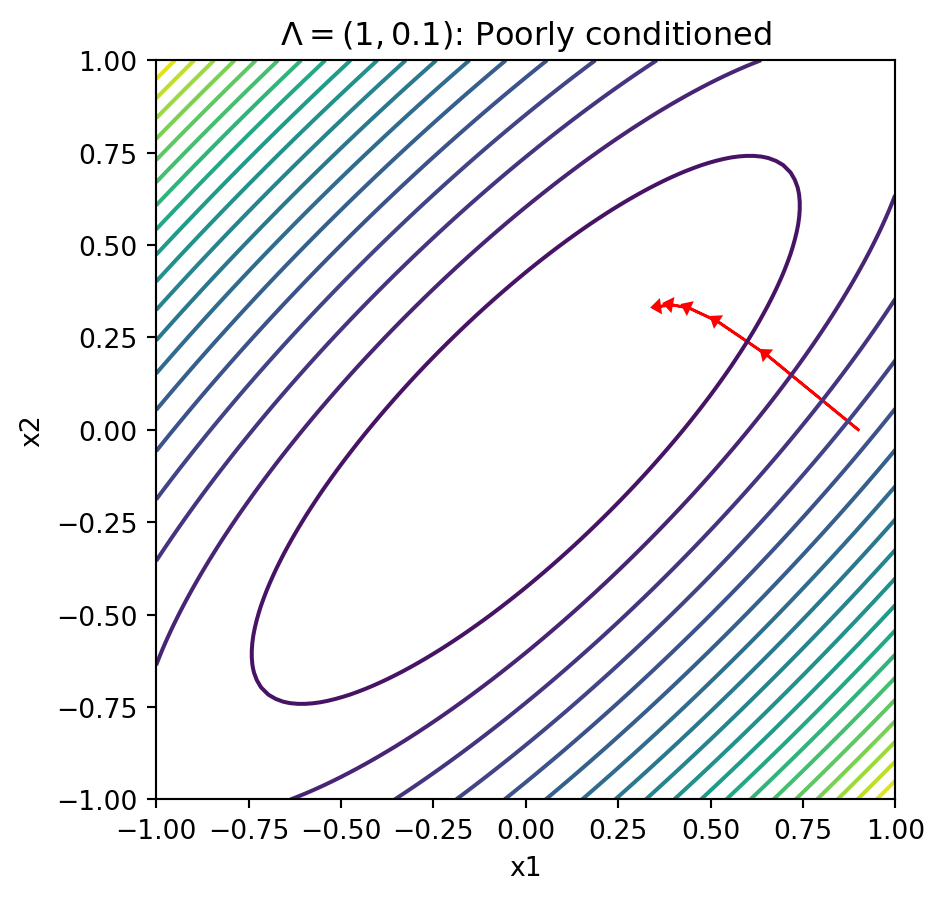

Contours Getting Closer to a “Ridge”

- Let \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(1, 0.1)\)

- Slow convergence in the “flat” direction

Contours Getting Closer to a “Ridge”

Text(0.5, 1.0, '$\\Lambda = (1, 0.1)$: Poorly conditioned')

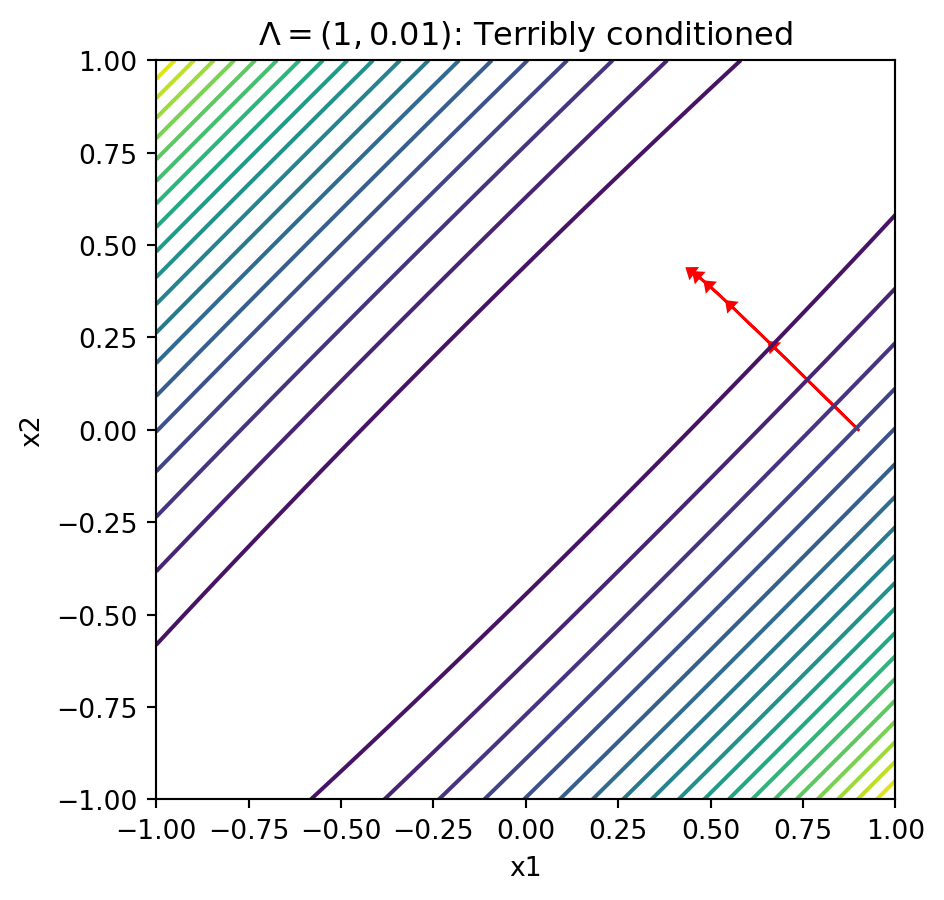

Contours With Terribly Conditioned Matrices

- Let \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(1, 0.01)\)

- Can barely move in the “bad” direction

Contours With Terribly Conditioned Matrices

Text(0.5, 1.0, '$\\Lambda = (1, 0.01)$: Terribly conditioned')

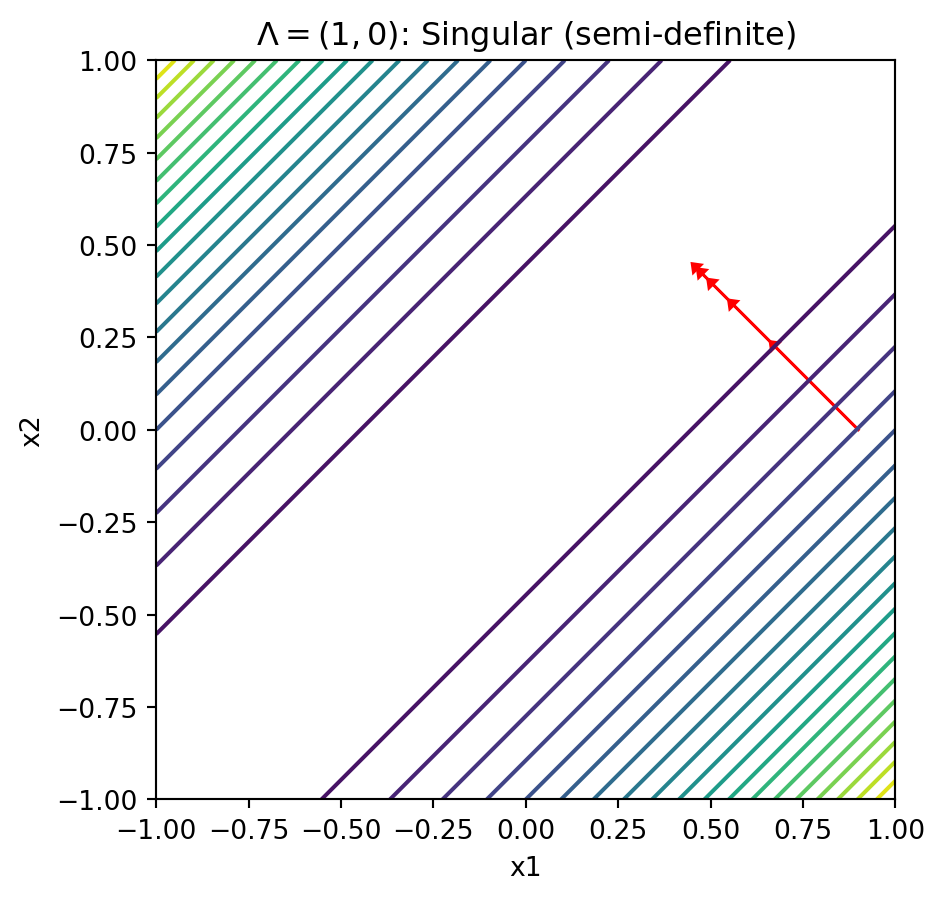

Contours With Ill-Conditioned Matrices

- Let \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(1, 0.0)\)

- Not full rank, positive semi-definite. But hits minima along the ridge

Contours With Ill-Conditioned Matrices

Text(0.5, 1.0, '$\\Lambda = (1, 0)$: Singular (semi-definite)')

Regularization and Large-Scale Methods

Motivation for Regularization and Conditioning

Geometry, not dimensionality, the key to understanding a large class of algorithms (anything you would use in high-dimensions)

- “Local” geometry is summarized by the “spectrum” of the Hessian

- In particular, wildly mismatched eigenvalues are the enemy

\[ \text{cond}(A) = \left|\frac{\lambda_{\max}(A)}{\lambda_{\min}(A)}\right| \]

Regularization: ridge \(\alpha \|x\|_2^2\) then spectrum becomes \(\lambda_i + \alpha\)

See more in Mark Schmidt’s Notes on Gradient Descent

Condition Number and Numerical Precision

- Rule of thumb: if condition number is \(10^k\), lose about \(k\) digits of precision

cond(X) = 1.34

cond(X.T @ X) = 1.80

cond(X_col.T @ X_col) = 1.65e+16Ridge Regression Stabilizes Conditioning

Iterative Methods for Large-Scale Least Squares

- For very large systems, direct methods become impractical

- The iterative methods lecture covers NormalCG and other Krylov methods

- Lineax

lx.NormalCG()solver for least squares via iterative methods - Key insight: same conditioning/eigenvalue concepts determine convergence rate

- Preconditioners transform the problem to improve conditioning